Simple Linear Regression with SAS

Contents

Introduction and Data

This example demonstrates how to perform simple linear regression using SAS. The data used in this demonstration is in a CSV file called kfm.csv. The variables are:

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

no |

A numeric vector, identification number |

dl_milk |

A numeric vector, breast-milk intake (dl/24h) |

sex |

A factor with levels boy and girl |

weight |

A numeric vector, weight of child (kg) |

ml_suppl |

A numeric vector, supplementary milk substitute (ml/24h) |

mat_weight |

A numeric vector, weight of mother (kg) |

mat_height |

A numeric vector, height of mother (cm) |

Data as CSV: Here is the complete data set, in CSV format.

"no", "dl_milk", "sex", "weight", "ml_suppl", "mat_weight", "mat_height"

1, 8.42, "boy", 5.002, 250, 65, 173

4, 8.44, "boy", 5.128, 0, 48, 158

5, 8.41, "boy", 5.445, 40, 62, 160

10, 9.65, "boy", 5.106, 60, 55, 162

12, 6.44, "boy", 5.196, 240, 58, 170

16, 6.29, "boy", 5.526, 0, 56, 153

22, 9.79, "boy", 5.928, 30, 78, 175

28, 8.43, "boy", 5.263, 0, 57, 170

31, 8.05, "boy", 6.578, 230, 57, 168

32, 6.48, "boy", 5.588, 555, 58, 173

36, 7.64, "boy", 4.613, 0, 58, 171

39, 8.73, "boy", 5.882, 60, 54, 163

54, 7.71, "boy", 5.618, 315, 68, 179

55, 8.39, "boy", 6.032, 370, 56, 175

72, 9.32, "boy", 6.030, 130, 62, 168

78, 6.78, "boy", 4.727, 0, 59, 172

79, 9.63, "boy", 5.345, 55, 68, 172

80, 5.97, "boy", 5.359, 10, 60, 159

81, 8.39, "boy", 5.320, 20, 59, 174

82, 10.43, "boy", 6.501, 105, 76, 185

83, 5.62, "boy", 4.666, 80, 52, 159

84, 6.84, "boy", 4.969, 80, 54, 165

90, 10.35, "boy", 6.105, 0, 78, 174

91, 4.91, "boy", 4.360, 0, 49, 162

98, 7.70, "boy", 5.667, 0, 63, 165

6, 10.03, "girl", 6.100, 0, 58, 167

14, 7.42, "girl", 5.421, 45, 67, 175

25, 5.00, "girl", 4.744, 30, 73, 164

26, 8.67, "girl", 5.800, 30, 80, 175

27, 6.90, "girl", 5.822, 0, 59, 174

34, 6.89, "girl", 5.081, 20, 53, 162

37, 7.22, "girl", 5.336, 590, 58, 160

38, 7.01, "girl", 5.637, 100, 63, 170

40, 8.06, "girl", 5.546, 70, 61, 170

41, 4.44, "girl", 4.386, 150, 58, 167

43, 8.57, "girl", 5.568, 30, 70, 172

46, 5.17, "girl", 5.169, 0, 65, 160

47, 7.74, "girl", 4.825, 210, 58, 176

56, 7.93, "girl", 5.156, 20, 74, 165

57, 5.03, "girl", 4.120, 100, 55, 162

63, 7.68, "girl", 4.725, 100, 50, 160

65, 6.91, "girl", 5.636, 30, 49, 161

66, 8.23, "girl", 5.377, 110, 55, 167

68, 7.36, "girl", 5.195, 80, 59, 171

74, 6.46, "girl", 5.385, 70, 51, 165

85, 7.24, "girl", 4.635, 15, 48, 167

88, 9.03, "girl", 5.730, 100, 62, 172

100, 4.63, "girl", 5.360, 145, 48, 157

104, 6.97, "girl", 4.890, 30, 67, 165

105, 5.82, "girl", 4.339, 95, 47, 163

The Task: perform a linear regression using dl_milk as explanatory and weight as response.

Before you begin

You may need to read the data from a csv file.

*You may need to read the data from csv file;

*Use firstobs=2 since there is a header;

data kfm;

infile "C:\Documents\kfm.csv" dsd firstobs=2;

input no dl_milk sex $ weight ml_suppl mat_weight mat_height;

run;

Explore the data: Plotting

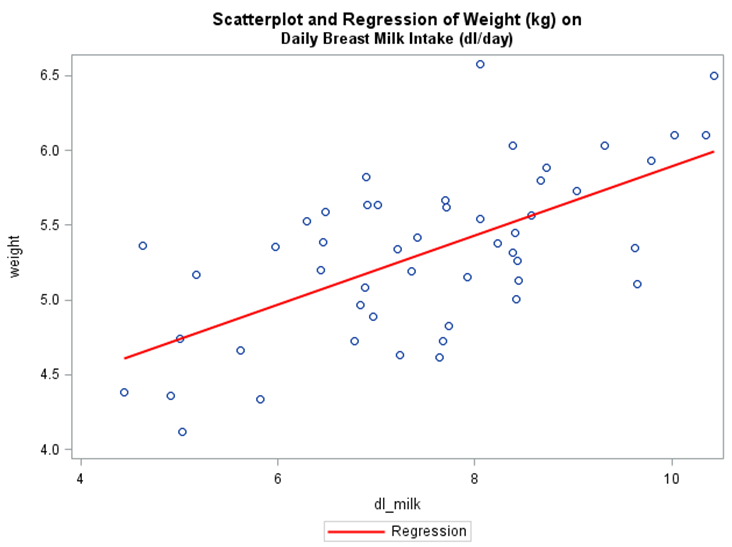

One of the most important first steps in any data analysis is to plot the data. The following code can be used to create a scatterplot in SAS and overlay a regression line. The code is also listed to overlay a LOESS, should this be necessary. [It is possible to use proc template to overlay both of these lines simultaneously]

title "Scatterplot and Regression of Weight (kg) on";

title2 "Daily Breast Milk Intake (dl/day)";

proc sgplot data=kfm;

reg x=dl_milk y=weight;

run;

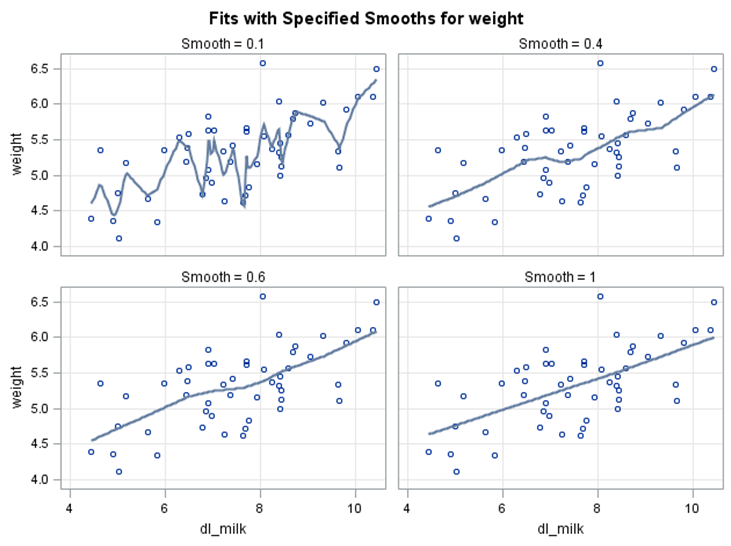

title "Scatterplot and Loess of Weight (kg) on";

title2 "Daily Breast Milk Intake (dl/day)";

proc loess data=kfm;

model weight=dl_milk / smooth=.1 .4 .6 1;

run;

The scatterplot does show evidence of a positive linear trend, indicating that as the amount of daily breast milk intake increases, weight tends to increase. The red line is the least squares regression line, which will be discussed in greater detail in just a moment.

The blue lines above are the lowess (locally weighted scatterplot smoothing) lines at various smoothing parameters. These lines attempt to fit a line to the scatterplot, with a lower parameter essentially “overfitting”. If this line is not relatively straight, it may indicate that simple linear regression (without any sort of transformation of variables) is not appropriate. Notice how the lowess lines appear relatively straight, even at low values of the smoothing parameter. In fact, it appears to be very close to the least square regression line at smooth=1. This indicates that simple linear regression may be appropriate.

Explore the data: Correlation

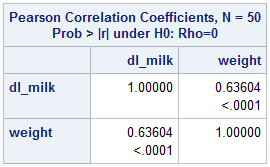

Correlation is a measure of the strength and direction of a linear relationship. The farther from 0 (and closer to 1 or -1), the stronger the relationship. The sign indicates whether the relationship is positive or negative.

title "Correlation Matrix for kfm data set";

proc corr data=kfm;

var dl_milk weight;

run;

The correlation is determined to be .636, indicating a moderately strong, positive, linear relationship. Furthermore, SAS reports the p-value here (<.0001). With a p-value this low, it is concluded that the true correlation is significantly different from zero. This supports the conclusions made above.

Verifying Assumptions

When performing linear regression, we have several assumptions to check:

1. Linearity: There is a linear relationship between the independent and dependent variables. (The mean of the Y values is accurately modeled by a linear function of the X values)

2. Normality of the Errors: The random error term is assumed to have a normal distribution with a mean of zero.

3. Homoscedasticity: The random error term is assumed to have a constant variance.

4. Independence of the Errors: The errors are independent of each other.

5. No Perfect Multicollinearity: (For multiple linear regression) There is no perfect collinearity between independent variables.

Let’s look at these one-by-one.

Linearity of the Relationship

It is necessary to assume that the mean of the response is a linear combination of the predictor variables. It is apparent from the initial exploration that these data exhibit a linear relationship.

Normality of the Residuals

It is important to assume that the residuals of the regression line are normally distributed. Though this assumption can often be rejected using a visual approach (in the case of residuals that are clearly non-normal), it is more appropriate to use a formal test for normality. In SAS, many of the assumptions can be verified within the regression itself.

title "Regression of Weight on Daily Breast Milk Intake";

proc reg data=kfm plots(unpack) plots(label);

model weight=dl_milk / dw vif clb alpha=.05;

output out=kfm_resid

r=resid;

quit;

run;

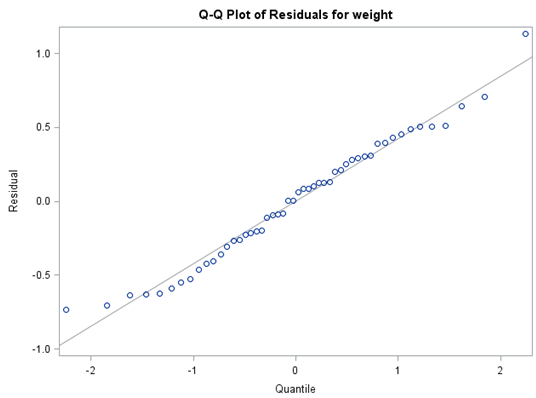

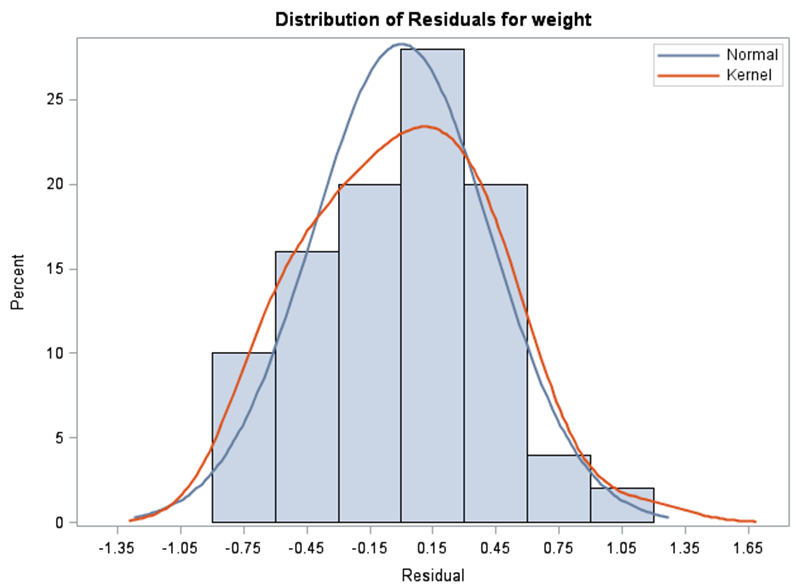

There is no reason to doubt the Normality of the residuals, as the Q-Q Plot appears linear and the histogram is relatively Normal. The output statement is used above to output the residuals to a new data set. This allows the user to perform a formal test for Normality, if necessary.

proc univariate data=kfm_resid normaltest;

var resid;

run;

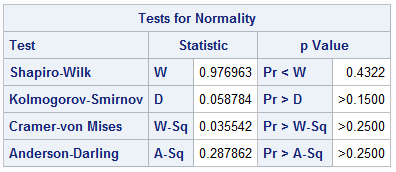

The output shows several different tests for Normality, all of which support the assumption of Normality. For instance, the Shapiro-Wilk Test for Normality (Null Hypothesis is that data are from a Normally distributed population) provides a w-statistic of .977. This corresponds to a p-value of .4322, which is not sufficient to reject the hypothesis of Normality. Therefore, it is concluded that the residuals are Normally distributed.

Homoscedasticity

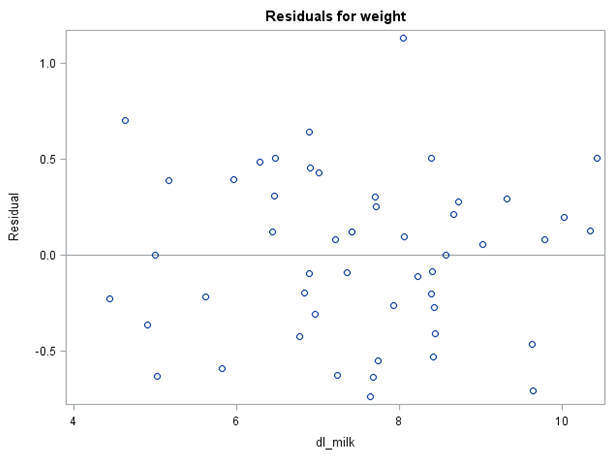

It is also important to verify that the variance of errors is relatively constant across all levels of the independent variable. In SAS, this can be accomplished by investigating the residual plot.

The graph does not show any evidence of fanning or pattern in the variance, so it is concluded that the assumption is met.

Independence of the Error Terms

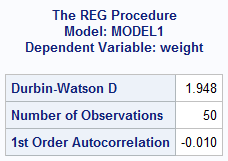

A Durbin-Watson test is one way to assess the condition of whether or not the errors are independent of each other. The null hypothesis is that the errors are independent (ie. They are not correlated). The statistic was already requested above in the proc reg function and appears as a “dw” after the model statement.

The Durbin-Watson test yields a statistic of about 1.95 (This corresponds to a p-value of 0.876). Generally speaking, a Durbin-Watson statistic of around 2.0 indicates independence, with deviations of ± 0.5 indicating autocorrelation. This result is not enough to reject the null hypothesis, so it is concluded that the errors are, indeed, independent.

No Perfect Multicollinearity

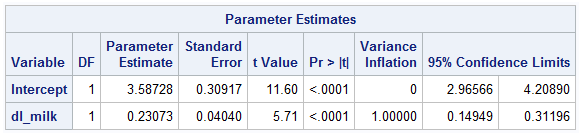

It is important to assume that there is no perfect collinearity between independent variables. This condition does not apply to this particular example, since there is only one predictor variable. If it were necessary, though, one way to verify this would be to calculate the Variance Inflation Factors. This calculation has already been requested in the proc reg function above, appearing as a “vif” in the model statement option. Keep in mind that if the square root of any variance inflation factor is greater than two, this condition may be violated.

Performing Simple Linear Regression

Now that all of the preliminary work has been completed, regression analysis can begin. There are a few things that can be completed to this end. The linear regression can provide an equation for the least squares regression line, which can then be used to interpolate or extrapolate predictions for weight. An ANOVA table can be constructed to determine the model’s overall utility. Also, a confidence interval can be calculated for the intercept and the independent variables. In fact, all of these tasks have already been requested above in the proc reg function (Parameter estimates and ANOVA table are produced by default, the 95% confidence intervals are requested by adding the clb alpha=.05 in the model statement options).

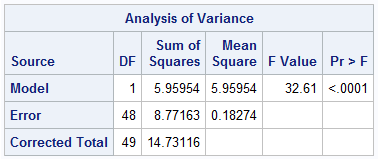

The ANOVA table provides an F-statistic of 32.61, which corresponds to a p-value less than .0001. This indicates that there are useful predictors present in the model (in this case, since there is only one predictor, it is often an indication that the variable dl_milk is significant).

Parameter estimates are provided in the table above, along with the 95% confidence estimations for each. The intercept is estimated to be 3.587 (between 2.966 and 4.209), while the coefficient for dl_milk is estimated to be 0.231 (between 0.149 and 0.312). The t-values are large in both cases, and thus correspond to p-values low enough to indicate the significance of the variables.

So the equation of the least squares regression line is weight=3.5873+dl_milk*.2307. This can be used to create a data set of predictions as follows:

data predictions;

input dl_milk;

cards;

1

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

7.0

;

run;

data predictions;

set predictions;

weight=3.5873+dl_milk*.2307;

run;

The values produced here can be used to predict weight as certain daily breast milk intake. Of course, one should always use caution when extrapolating.

Further Exploration—Influential Points and Outliers

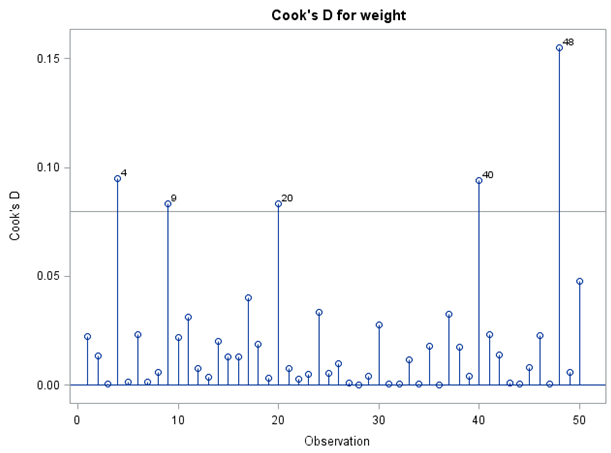

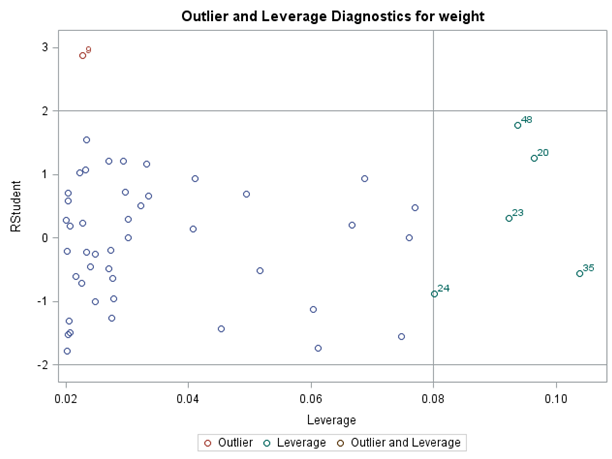

The Cook’s D plot reveals that observations 4, 9, 20, 40, and 48 are influential observations. However, the influential plot indicates that only observation 9 is an outlier while identifying observations 20, 23, 24, 35, and 48 as influential. All of these points should be flagged for further investigation.

Conclusion

We hope you found this guide to simple linear regression in SAS useful!